Practitioner Notes

1. What is already known about the topic

-

Child protection practices are critical measures designed to safeguard children against violence, abuse, neglect, and exploitation in school environments.

-

Effective child protection practices involve creating safe and nurturing environments that allow children to thrive.

-

Collaboration between schools and child protection agencies is essential to enhance child protection practices.

-

The Social Capital theory emphasizes the importance of social relationships, trust, and mutuality in collaborative efforts for child protection.

2. What this study contributes

-

This study provides empirical evidence on collaboration between schools and child protection agencies in pre-primary schools in Kira Municipality, Uganda.

-

It identifies specific gaps and challenges in the collaboration efforts, highlighting areas where schools and child protection agencies are not effectively working together.

-

The study presents concrete recommendations for improving collaboration and child protection practices, including joint planning, capacity building for educators, increased resources, and advocacy for better laws and policies.

3. Implications for practice and/or policy

-

Schools and child protection agencies should prioritize establishing and maintaining strong collaborative frameworks to enhance child protection practices.

-

Comprehensive child protection policies need to be developed, regularly updated, and integrated into school operational frameworks.

-

There is a need for confidential and accessible reporting mechanisms for children, parents, and teachers to report incidents of abuse and neglect.

-

Schools should conduct regular safety audits and provide ongoing training for teachers and staff on child safety and protection issues.

-

Policymakers should focus on providing adequate resources and financial support to promote child safety and protection.

-

Advocacy for laws and policies that uphold children’s rights is crucial to ensure a protective and supportive environment for children’s development.

Introduction

Lack of protection and vulnerabilities caused by different types of traumas and child abuse during the first years of development critically affect the child’s well-being (Bartlett & Smith, 2019). Child protection programs are intended to prevent and respond to harm that affects the child’s well-being (Asio et al., 2020). The East African Community Secretariat (EACS) (2017) defines child protection as measures that prevent and respond to all forms of abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence against children in development and emergency settings. The authors have identified a child as a person below the age of eighteen. However, this study targeted children aged three to six (3-6) years. According to the East African Community (EAC) secretariat (2017), children constitute 50% of the EAC population. Each of the children deserves a right to development, survival, participation, and protection, as highlighted in the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACRWC). The East African Community Secretariat (2018) observes children in the EAC experience numerous challenges. Therefore, many efforts are needed to address such challenges that affect children.

The EACS (2018) suggests that children require systems that are comprehensive and determined by themselves. It is for that reason that the EACS has come up with the EAC Child Policy to strengthen and act with a common understanding on issues of child protection, provide guidance to all EAC states, integrate child protection into country plans, and develop frameworks that support teachers and other service providers to assess child safety and protection systems (EACS, 2018). In terms of implementing child protection practices at the earliest stages, pre-primary schools stand at the forefront. Still, they implement the activities collaboratively to make the services more inclusive. This implies that pre-primary teachers and educators at other levels should be empowered to implement child safety and protection practices effectively in schools and the entire community.

The EAC observed a gap in the safety and protection of its young people (EACS, 2018). In this aspect, partner states are called upon to work closely in partnership in social welfare concerning the development and adoption of a common agenda towards marginalized groups, including children. The EAC is an inter-governmental organization comprising six Partner Countries: Uganda, the Republic of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, and the United Republic of Tanzania. Child protection and well-being, or its absence at the beginning of life, determines children’s further development and lifelong learning (Toros et al., 2021). Correspondingly, research specifies the consequences of child abuse and neglect in the early years (Farrell & Walsh, 2010). Teacher training institutions should be aware of this area to ensure that teachers across levels are prepared to collaborate and integrate holistic packages that support delivering quality services.

In Africa, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) emphasize children and youth development with a significant focus on enabling children to access essential services, child safety, and inclusive protection (Jailobaeva et al., 2021; Raikes et al., 2017). The authors identified violence against children to be increasingly documented as a critical barrier to the attainment of the SDGs. An observation was made that over one billion children are annually exposed to violence and abuse in various ways (Jailobaeva et al., 2021). Similarly, the protection of children can be best achieved during the initial stages rather than later in adulthood (Spratt, 2001). Therefore, teachers and other loving adults must identify children with protective challenges early (Green et al., 2018, 2020; Kovan et al., 2014).

Implementation of effective child protection practices and interventions in schools and communities can uphold children’s rights, safety, and well-being (Toros et al., 2021). However, the success of effective child protection practices cannot be realized by one agency working solely; it requires different stakeholders to work collaboratively (Toros et al., 2021). Villagrana (2023) recognizes interprofessional collaborations as significant, especially in challenging situations. The Social Capital theory informed this. According to Claridge (2018), humans have been identified to be social organisms that evolve to be social and work together for collective action. Many things that people need cannot be created solely; they require collaborative efforts or work in a relationship. The concept of working together in partnership is called social capital (Claridge, 2018). The author observes social capital to come from human efforts to support others and complement what they have done or worked on in partnership. Therefore, Claridge (2018) recommends that the social capital theory be appropriate for any researcher studying human sociability and collaboration and its development.

Claridge (2018) attributes the social capital theory to the three authors, who all approached social capital from different perspectives. The three authors included Pierre Bourdieu, acknowledged for the Theory of capital; James Coleman, identified for the rational-choice approach; and Robert Putnam, recognized for the Democratic or civic viewpoint. Besides other authors, Putnam (2000) acknowledges that the Social Capital theory originated from different economists and sociologists. The modern theoretical framework is credited to researchers such as Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, and Robert Putnam. Claridge (2018) identifies that social capital begins from its fascinating mix of sociology and economics.

The Social capital theory emphasizes resources and the benefits resulting from social networks and relationships (Putnam, 2000). In the situation of school-child protection agency collaboration, the social capital theory points out the significance of building trust, mutuality, and cooperation between schools and child protection agencies.

Social capital requires the active involvement of stakeholders in planning and decision-making processes, as well as initiatives that affect the safety and well-being of children in schools and elsewhere (Shier, 2001). Social capital offers a framework that enables an understanding of a variety of occurrences beyond a fiscal lens, and in such a situation, more interventions for inter and transdisciplinary integration are put across (Adam & Roncevic, 2003; Claridge, 2018). In such circumstances, child protection systems must be empowered to respond to the pressing demands in schools and communities (Villagrana, 2023). Similarly, early childhood stakeholders responsible for managing children’s safety and protection serve as essential linkages for child protective services, especially for children who need them (Toros et al., 2021). This enables identifying and providing information on children’s safety and protection challenges (Welbourne & Dixon, 2016). However, the authors observe ideas on child safety and protection in early childhood that vary from place to place. It depends on the geographical location, context, socioeconomic status, cultural beliefs, religious background, and political situation (Welbourne & Dixon, 2016). All these affects how societies treat their children and the community’s role in the children’s safety and protection.

Villagrana (2023) highlights that much as other children experience child abuse and neglect, children and youth with a disability have been observed to have higher rates of substantiated mistreatment and are most likely to experience neglect and child abuse. Welbourne et al. (2016) contend that if children are not supported, their lives remain in danger. Some of such hazards and risks include accidents, child kidnaps, violence against children, child labour, and abuse, all of which affect children’s well-being. Both countries and societies can endorse visionary laws to protect children, most especially the youngest and those with disability at various locations. For instance, in schools and elsewhere, there are numerous stories where children are bullied and mistreated by their fellow children and corporal punishments by teachers, including other staff members (Asio et al., 2020). The authors identify the need for teachers and early childhood proprietors to be aware of child protection policies and implement child protection practices in schools to ensure children are safe and well protected. This implies that teacher training institutions should develop interventions that enable the production of quality pre-primary teachers. Such educators should be able to develop strategies that enhance positive discipline, including promoting safe and child-friendly spaces in schools.

Purpose of the Study

The study examined school-child protection agencies’ collaboration on child protection practices in pre-primary schools in Kira Municipality, Wakiso District in Uganda.

Objectives of the Study

The following objectives guided this study:

- Investigate the contribution of School-child protection agencies' collaboration on child protection practices in schools.

- Establish the different child protection practices that the school does with support from the various child protection agencies.

- Assess the relationship between the school-child protection agencies' collaboration and child protection practices in schools.

Research Questions

- What is the contribution of School-Child protection agencies' collaboration on child protection practices in schools?

- What are the different types of child protection practices done by the school and the child protection agencies?

Methodology

An evaluation of school-child protection agencies’ collaboration on child protection practices in pre-primary schools was conducted, targeting children between three and six (3-6) years of age. A descriptive cross-sectional survey design was employed using both qualitative and quantitative methods in data collection and analysis. The design was used because it was suitable for gathering data about people and their preferences, opinions, attitudes, and behaviour, reinforcing data generalization in an organized way (Bhattacherjee, 2012; Creswell, 2014). Quantitative and qualitative approaches were used in the data-gathering process. The design enabled the collection of data, its examination, and analysis at the same point in time. Besides that, the design was used to provide a snapshot of the current state of school-child protection agencies’ collaboration, types of child protection practices in schools, and the factors influencing child protection agencies’ cooperation with schools.

For the third objective, a cross-sectional survey design was used to obtain the data. The cross-sectional survey allows a researcher to collect data from the population or a representative subject at a specific point in time (Dannels, 2018). The cross-section survey design enables the researcher to attain a higher response rate (Kothari, 2004) since the researcher does not need to visit the respondents more than once.

A descriptive analysis was used to review and designate the results. This included calculating the occurrences, and percentages, and identifying themes. The descriptive results were interpreted to increase perceptions of the level and nature of child protection agencies’ collaboration in implementing child protection practices in schools. The collaboration levels were compared across the diverse demographic clusters and the level of schools. For example, the child protection agencies’ level of education informs the kind of results and the disparities or differences in the collaboration and pattern ship patterns.

The study involved an investigation of the various records in the pre-primary schools to establish whether school-child protection agencies’ collaborations are utilized to improve child protection practices in schools. Such records included visitors’ books, ECD policies and guidelines, work plans, school development plans, minutes, and attendance lists of the meeting stakeholders. Mills (2007) recognized document analysis as dependable in giving broader pictures of what had previously been done in line with the study. During the document scrutiny process, a guiding document was developed to identify documents describing the involvement and engagement of the various stakeholders in implementing child protection practices in Pre-Primary schools. Since the study was a survey aimed at generalizing findings, the questionnaire methods were used to collect large amounts of data. The observation method was used while collecting data from the observable components of the study. This was on both documents and activities that informed the study. In addition, using an interview guide and interviews were used to generate qualitative data. This included interviewing selected headteachers, Local leaders, Centre Management Committee chairpersons, and probation officers from the various police stations in Kira Municipality.

According to Tetui et al. (2021), the projected population of Kira Municipality was over 400,000 residents, whereby 47.8% were male, while 52.2% were female. The unit of analysis was the pre-primary schools located in Kira Municipality in Wakiso district, Uganda. The central unit of inquiry was the Headteachers of the selected pre-primary schools, given their role in initiating and sustaining partnerships and collaborations with key stakeholders. The study population targeted stakeholders that deliver services to pre-primary children between the ages of 3-5 years. The overall targeted study population comprised 345 Participants. Out of these, there were 150 headteachers of pre-primary schools. Given the targeted population, the researcher worked with a study sample of 257, and out of these, 108 were pre-primary headteachers, and 149 were other stakeholders. The sample selection was in line with Kreijce and Morgan’s (1970) table of sample selection. The 149 stakeholders included Probation Officers, Local Council members, and Centre Management Committee (CMC) chairpersons, all from Kira Municipality. The headteachers were randomly selected using the lottery method. The teachers who were involved, as assigned by the headteacher, were selected based on their qualifications.

The determinant of the sample size was to ensure that it was representative of the sample population. In this aspect, purposive and simple random sampling was used to select the schools and participants to contact. Table 1 summarizes the study sample size and sampling technique.

The researcher constructed items for the interview guides, observation checklists, and document analysis guides to collect data for objectives one and two, as well as a self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) used to collect data for objective three. The data collection instruments entailed items that evaluated the frequency and categories of child protection practices in school that are done in collaboration with child protection agencies, their perceptions on the importance of child protection practices, and the stumbling blocks that affect the cooperation and partnerships between the school and child protection agencies. The SAQ allowed respondents to respond to the questionnaire items at their own pace freely. The responses on the SAQ followed a Likert scale of 1-5, with a score of 1 representing strongly disagree and five representing strongly agree. Score 3 signified a neutral status. In this study, the decision criteria to guide the process of interpreting the results was a mean of 3.5 and above to represent agree and a mean below 2.5 to represent disagree. The Mean scores between 2.5 and 3.4 are considered neutral on the item. The research instruments were used to help accomplish the study’s objectives. The instruments comprised an observation checklist, a document analysis guide, interview guides, and questionnaires.

Additionally, different instruments were used to compare the responses given by the various stakeholders and participants for validity and trustworthiness (Hendricks, 2009). The author recognized that triangulation could establish trustworthiness, which allowed multiple forms of data collection and analysis. Qualitative and quantitative studies were used to collect data. During the study, document analysis guides were used to collect data from the accessible records in the pre-primary schools. Document analysis was identified as credible in understanding the various interventions previously done in the study (Mills, 2007). Interview guides were used to collect detailed qualitative data from key informants. This was recorded both textually and audially. Interviews supported getting in-depth information and explanations on the ongoing child protection practices. The interview also helped generate helpful details that should have been planned for earlier.

Questionnaires were part of the instruments that were used for data collection. The developed questions were considered a way that enabled respondents to ably read, understand, and quickly eloquently respond to them. They comprised a set of questions prearranged to capture answers from the targeted people consistently and simply on matters regarding School-child protection agencies’ collaboration and child protection practices in schools. The observation checklists were used to validate what was going on at the Pre-primary school in line with the study; for example, the general school environment set up, outdoor and indoor classroom space as aligned to the Basic requirements and minimum standards, photos and pictures in offices and the classrooms and the probation offices, and other sources plus activities that were going on within the school that were aligned to the area of child safety and protection. Correspondingly, schools keep photos as evidence of what has occurred within the school. These were used as evidence for child protection practices that had taken place during the study process. Hendricks (2009) emphasized that observations could be used to identify evidence of the various activities related to the study area and strengthen the findings. The study variables were measured using item scales developed by previous scholars and adapted to fit the study context. The reason for doing this was that the item scales were developed in advanced countries.

To ensure validity and reliability, the researcher established the validity of the study instruments using the content validity index (CVI). For instance, the self-administered questionnaire (SAQ) and the rest of the instruments were given to two experts in the Ministry of Education and Sports (MOES) in pre-primary education and, at the same time, familiar with partnerships and collaborative networking. The experts rated the items in the questionnaires and other instruments as relevant or not relevant. The items rated relevant by both were counted and expressed as a percentage of the whole instrument. The experts agreed on 21 of the 26 items in the instrument, giving a CVI of 0.86. According to Yusoff (2019), a CVI of at least 0.70 is acceptable. This implies that our instrument was highly valid.

To establish the reliability of the instruments, the researchers conducted the Cronbach alpha test on them. The qualitative data was cleaned, coded, and organized into themes that answered the research questions to which they were addressed. After organizing the data, thematic content analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data. At the same time, the alpha result obtained was 0.9. Creswell and Miller (2000) suggest that a reliability index 0.70 is acceptable. This implies that the instruments were highly reliable. The instruments were pilot-tested, and 15 headteachers were excluded from the final sample. The statistical treatment of data collected using the SAQ was edited, coded, and analysed with the help of STATA 14 software. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were generated. The regression analysis was guided by the equation Where; Dependent Variable (Health Care Practices-HCP), Independent Variable (School health service providers’ collaboration -SHSP), Error term (helps to explain the unexplained variations in the model), and is constant term while the coefficient was used to measure the sensitivity of to unit change in the The instruments were presented to faculty for approval and in case of any area that required corrections, the researcher worked on it together with the supervisors. Besides that, the research proposal was submitted for ethical clearance to the Internal Review Board (IRB). The ethical principles of identification, anonymity, privacy, confidentiality, and informed consent were observed throughout the research process.

During the study, respect for participants’ rights was put into consideration. This entailed controlling their involvement, lessening risks to the participants, and avoiding selecting them because of peripheral paybacks (Trainer & Grauce, 2013). During the study, the researcher observed the recognized measures of the Ethical Review Committee of Kyambogo University throughout the study. Permission was obtained from the responsible ministries, departments, and agencies. This included the Ministry of Education and Sports, the Ministry of Science and Technology, Kira Municipality, site head teachers at the Pre-Primary schools where the research was conducted, and the various institutions within the community. The information gathered was kept private for only research purposes. Only pseudonyms and codes have been used as agreed.

Results

The study revealed that school-child protection agencies’ collaboration promotes child protection practices in schools. Although it was not efficiently done in schools, many of the respondents acknowledged that if schools work in partnership with child protection agencies, it could mitigate issues of child abuse, violence, discrimination, and mistreatment. Besides that, it would promote effective child protection practices within the school environment and elsewhere and value issues concerning children’s mental and physical health. Furthermore, child exploitation and neglect would be avoided within schools and communities, hence reducing issues that affect children’s holistic development, which could last a lifetime throughout their adulthood—hereafter, having assured the safety and well-being of all children.

Data was collected using observations, interviews, questionnaires, and document analysis. Throughout the observations, much concentration was put on the types of child protection practices seen in the classrooms, offices, and the school compound. This included the activities, infrastructure, and any pictures or photos related to safety and child protection. These included the approaches used and the stakeholders with whom the school collaborates in promoting child protection practices. In the case of any stakeholder that came into the school, the researcher was conscious of understanding what he or she had come to do in the school. The researcher noted it in the diary in case it was related to child safety and protection. It was observed that some parents dropped their children off in the morning, and when it was time to go home, teachers made children sit in one place to wait for the parents or guardians. This kind of observation was made in almost all the schools. However, the actions in all the schools were different. The mode of programs differed from one school to another. In some of the schools, as these children were very young, they came to school and went back home by themselves. To verify the observations, interview sessions were conducted with the various stakeholders that had been highlighted to promote child protection practices. The interviewed stakeholders comprised Headteachers, Centre management committee (CMC) chairpersons, Probation officers, and Local Council (LC) members.

Headteachers, CMC chairpersons, Probation officers, and LC members were involved during the interview. The information shared discovered that, much as they knew the importance of collaborating with child protection agencies and probation officers working in partnership with the school, they hadn’t been putting much emphasis on it. Most schools reflected that they did not fully utilize the probation officers and other child protection agencies, although they knew how important they were. The probation officers reported that they would love to collaborate with the schools. However, they claimed they did not have the facilitation to contact all the schools. They only had an opportunity to reach out to the schools when the District Police Commander (DPC) was deciding in the Municipality or when the schools that needed them provided support. The schools majorly engaged them on issues concerning child abuse or neglect when some of the parents had resisted clearing school dues when children had gone missing from their homes or school or in case of any accidents. This was realized when Probation Officer No.1 (PO/1) stated:

“We would have loved to reach out to all the schools, especially to train parents and staff on child safety and protection issues. The challenge is that we lack facilitation; even the responsible Ministry only calls when a child has a problem but still without any facilitation. This makes our work very difficult. And as of now, so many children are being abused even by their parents”.

In addition, the probation officers highlighted areas in which they were guiding child safety and protection. This included churches, mosques, community groups, and police stations. For instance, talking to the public about how they should treat their children in preparation for their future, encouraging them always to attend prayers with children, preparing children’s minds to mitigate criminal offenses, and for elders to behave well before children to have good morals. Such as respect and mitigate violence against children at home and within the community. However, such interventions were rarely done in schools because the probation officers lacked facilitation. This was observed when probation officer number 2 (PO/2) stated:

“We don’t have a lot of resources. We only use an opportunity of the Community Policy. When we get a chance to reach out to the school or within community meetings, we give children examples of strong role models so that it helps them to behave well and stay in school”.

Probation officer number 3 (PO/3) stated:

“Due to a lack of enough resources, the few schools invite us during parents’ meetings to orient them on how to take full responsibility for their children’s safety and protection. Most especially when they are on their way to school, from school, and within the community. In addition, they use police to help them solicit children’s fees”.

The probation officers highlighted that they would be the ones to fully provide support for the safety and protection of their people both in the community and in schools. This was observed when probation officer number 5 (PO/5) stated:

“It would be our role to manage the safety and protection of children both in schools and within the community. For example, transportation of children to and from school and violence against children in school and within the homes, but our hands are tied. We do not have facilitation. If we had it, we would list schools and contact them”.

In addition, some headteachers clarified that they work with the parents on the safety and protection of their children. This was mainly done by encouraging parents to drop off and pick up their children from school. They also outlined that they work closely with agencies supporting early childhood education. However, this was observed in only a few schools. Schools were working closely with Centre Management Committee (CMC) members and Local Council 1 (LC1) members to create linkages with child protection agencies to strengthen child safety and protection systems. For example, this was observed when headteacher school number 1 (HTR1-SCH1) stated:

"We have been working with the CMC members to mobilize the probation officers and the fire brigades to train the teachers and non-teaching staff in identifying risk areas that can cause fire outbreaks and how to use fire extinguishers.

A document analysis guide analysed minutes, attendance lists, schoolwork plans, reports, and school improvement plans. The findings showed that although schools blamed the child protection agencies for not working together with schools to promote child protection practices in schools, the documents that were analysed in the schools needed more components on child safety and protection. Neither the work nor school improvement plans included child safety and protection-related issues. Similarly, neither the minutes nor the attendance lists reflected any participation of the child protection agencies in most of the schools. After thoroughly analysing the instruments, the data was recorded and analysed to produce the results.

After data collection, the responses were tabulated in numerical form, showing percentages of those who had evidence of child protection practices in schools and those who didn’t. The presented data was analysed using descriptive statistics and presented in tables.

Table 2 above presents data on evidence of the availability of child protection policies at the school to guide the collaborations required to promote child protection practices in the schools. The data showed that 78.7% of the schools did not have the ECCE policy, whereas 21% used it to guide the collaborative networking and promotion of child protection practices. 60.1% of the schools still needed school-based child protection policies to guide school-level collaborations and child protection practices. In comparison, 39.8% had school-based child protection policies to guide school-level collaborations and child protection practices. Evidence showed that 89.8% of the schools did not have children’s Birth Registration Certificates against 10.1% that had Birth Registration Certificates. Besides that, 58.3% of the schools had work plans that did not reflect child safety and protection issues, whereas 41.7% had problems that talked about child protection but did not bring out the element of collaboration and networking. Lastly, 44% of the schools didn’t present any minutes at the time of the field visits, while 57.5% had minutes but without any sign of collaboration and partnerships shown.

Descriptive statistics

Our third objective guided the descriptive statistics. The corresponding hypothesis was Ho: There is no relationship between School-child protection agencies’ collaboration and child protection practices in schools. The hypothesis was tested using the correlation results in Table 3. The type of collaboration between the school and child protection agencies is presented in Table 3, while the child protection practices are presented in Table 4.

Table 3 provides statistics on the type of collaborations between schools and child protection agencies. For the collaboration to increase children’s enrolment in pre-primary schools, the Mean was 4.06, with a standard deviation of 0.43. The mean score suggests a high level of collaboration on increasing children’s enrolment, with low variability in responses.

The collaboration with parents on the safety and protection of children reflected a mean of 4.54 with a standard deviation of 0.55. The mean score indicates a high level of collaboration on providing TL materials in pre-primary schools with low variability in responses.

The mean score for collaboration on the safety and protection of children in pre-primary schools to enhance their rights was 3.24, with a standard deviation of 0.88. The mean score suggests a high level of collaboration on safety and protection measures to improve children’s rights, with low response variability.

The mean score for collaborating with child protection agencies and parents on providing protective gadgets in pre-primary schools was 3.93, with a standard deviation of 0.59. This implies a general agreement among the respondents with limited variability in responses. The mean score for the collaboration on the general child protection and well-being of children and staff in pre-primary schools was 4.30, with a standard deviation of 0.57. The mean score indicated a high level of collaboration on child protection and well-being initiatives for children and staff. The responses showed low variability.

The mean score in collaboration with resource mobilization to support the delivery of child protection practices was 4.06, with a standard deviation of 0.30. The mean score indicates a moderate level of collaboration on resource mobilization to support the delivery of child protection practices, with considerable variability in responses. In partnership with law enforcement officers in pre-primary schools, the mean score was 4.02, with a standard deviation of 0.39. The mean score suggests a high level of collaboration in law enforcement, with low response variability.

Collaboration on the enforcement of children’s rights for children three to six years old who attend pre-primary school: The mean was 4.80, with a standard deviation of 0.45. The mean score indicates a high level of collaboration on enforcing children’s rights within pre-primary schools, with low response variability.

In the collaboration on the implementation of child protection policies in pre-primary schools, the mean was 3.94 with a standard deviation of 0.80. The mean score suggests that the existence of a very high level of collaboration on policy implementation. The variation in the responses was low.

Collaboration with the local council (LC) to support the school in mobilizing child protection agencies to deliver child protection services in pre-primary schools; the mean was 4.09 with a standard deviation of 0.73. The mean score indicated agreement among the respondents in school collaboration with Local Councils (LC) on delivering child protection services. The variation in responses was low.

The school’s collaboration with child protection agencies in training staff and parents on child protection-related issues was measured; the mean was 4.44, with a standard deviation of 0.75. This shows agreement among respondents on the high collaboration between the school and child protection agencies in training staff and parents in pre-primary schools. The variability in responses was low.

The mean for collaboration with stakeholders on creating linkages between the school and child protection agencies for staff and children within the pre-primary schools was 2.89, with a standard deviation of 0.96. The mean score suggests that the respondents were neutral regarding the area of collaboration in this area. The variability in responses was low.

Regarding collaboration, feedback sharing, and strengthened coordination amongst stakeholders within pre-primary schools, the mean was 3.94, with a standard deviation of 0.49. The mean score indicates agreement among respondents that collaboration exists in sharing feedback and strengthening coordination amongst stakeholders, with a relatively low variability in responses.

The collaborations contributed to an improvement in allowing children to carry out various physical exercises to enable them to grow and develop with a healthy and strong body; the mean was 4.77 with a standard deviation of 0.424. The mean score indicates high opportunities for children to carry out physical exercises, with low variability in responses.

Promoting children’s creativity and well-being through arts/crafts and play was used to reduce children’s stress and trauma and protect them from danger. In this aspect, the mean was 4.71, with a standard deviation of 0.454. The mean score suggests a high level of promoting children’s creativity and well-being through art, craft, and play within pre-primary schools, with low response variability.

Through collaboration, children participated in role-play and imagination activities in which they were able to imitate child protection practices. In this aspect, the mean was 4.69, with a standard deviation of 0.482. The mean score indicates a high level of engagement in role-play and imagination activities among children, with low variability in responses.

Child participation in drama was observed to enhance child protection practices in pre-primary schools. The mean was 4.79, with a standard deviation of 0.411. The mean score suggests a high level of child participation in drama activities to enhance child protection practices, with low variability in responses.

The mean of children’s involvement in emergent child protection activities in pre-primary schools was 4.31, with a standard deviation of 0.486. The mean score indicated a relatively high level of involvement, with moderate variability in responses. The mean of the pre-primary schools’ participation of children in critical thinking, problem-solving, inquiry skills, and child protection skills to mitigate challenges to child protection practices was 4.7, with a standard deviation of 0.459. The mean score suggests a high level of children’s involvement in critical thinking, problem-solving, inquiry skills, and protection skills, with low variability in responses.

Engagement of stakeholders in coordination activities to strengthen child protection activities and self-expression activities for children in pre-primary schools. In this aspect, there is a mean of 3.01 with a standard deviation of 0.902. The mean score implies a neutral response regarding the level of engagement in coordination and self-expression activities among children. The variability in the reactions among the respondents was low.

The school has comprehensive policies on child protection activities for children, staff, and parents, with a mean of 3.54 and a standard deviation of 0.836. The mean score suggests the neutral position taken by respondents on the level of implementation of comprehensive child protection policies in schools. The variation in responses was low.

Teachers and parents’ recognition of signs of child abuse and neglect in pre-primary school had a mean score of 4.09 with a standard deviation of 0.322. The mean score indicated a high level of recognition of signs of child abuse and neglect among teachers and parents, with low variability in responses.

Regular updates to children, staff, and parents on child protection issues and child well-being in pre-primary schools. The mean score was 4.23, with a standard deviation of 0.523. The mean score suggests regular updates on child protection issues and well-being to children, staff, and parents. The variability in responses was low.

The mean score on maintaining physical safety and protecting the school environment in pre-primary schools was 4.68, with a standard deviation of 0.47. The mean score indicated high physical safety and protection maintenance in the pre-primary school environment, with low response variability.

Children are adequately supervised and monitored to mitigate accidents, conflicts, and incidents of harm in the pre-primary school. The mean score was 4.72, with a standard deviation of 0.508. The mean score suggested a high level of adequate supervision and monitoring of children to prevent accidents, conflicts, and incidents of harm, with low variability in responses.

The mean of stakeholders’ training on severe child protection issues was 2.55, with a standard deviation of 0.89. The mean score indicates a low level of stakeholders’ training on severe child protection issues, and the variation among respondents was low. These statistics provide insights into the central tendency and variability of responses for each variable, which enabled an understanding of the level of collaboration in the various aspects, such as child safety and protection, child protection policies, practices, and training priorities in pre-primary schools.

The results indicate a significant positive relationship between SCP (0.719; p<0.05) and CCP in schools.

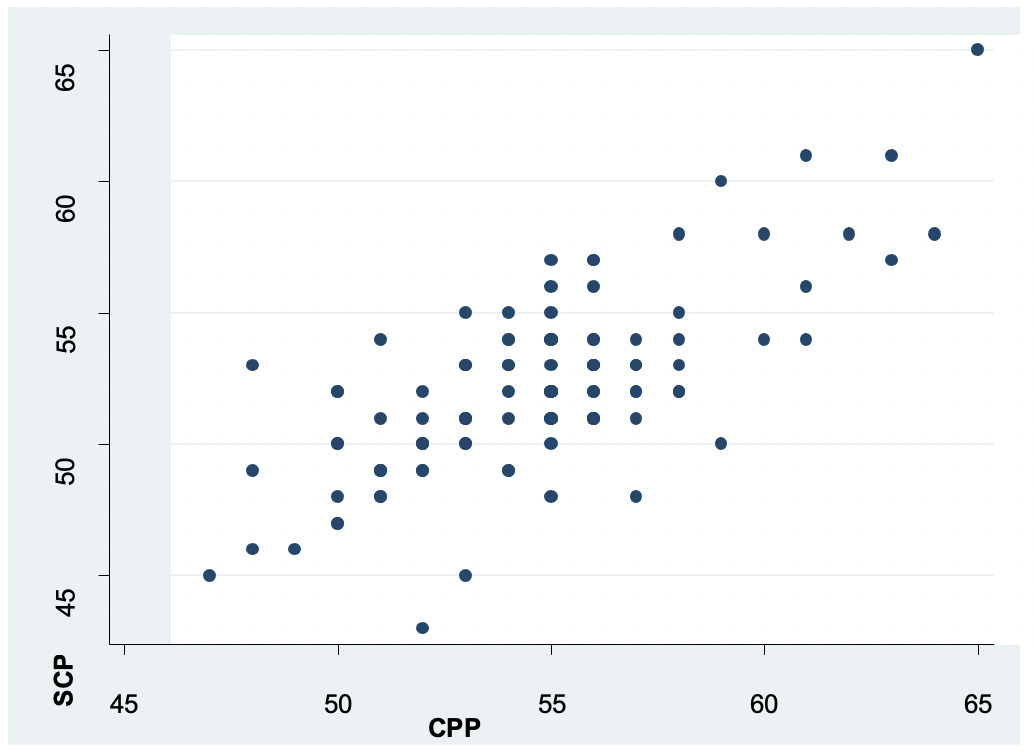

The figure shows that the collaboration between the school and child protection agencies is positively related to child protection practices.

The figure shows that the success of Child protection practices (CPP) in schools is positively related on the school child protection agencies’ collaboration.

The estimated equation is given as Y = 16.975 + 0.72X. These findings imply that for every one-unit increase in school-child protection agencies collaboration, the child protection practices in schools improve by 0.72. This means that the partnership between schools and child protection agencies improves the child protection practices in schools.

Collectively, the predictor variable explains 51.2% of the variation in child protection practices in schools (Adjusted R-squared 0.513; p<0.00). The difference between the R –and adjusted R- squared is only 0.004, meaning the model fit is perfect. The F-test is also significant, implying that our regression equation fits the data set used in the analysis well.

The collinearity tolerance (1/VIF) for the predictor variable was greater than 0.1(10%), with the corresponding variable inflation factor (VIF) equal to 1.00. This falls within the recommended interval of 1 and 10, indicating the non-existence of multicollinearity in our data set.

Discussion

Pre-primary learners have been observed to be among the children within the most sensitive period of growth and development (Black et al., 2017). Response to child safety and protection can only be achieved through various stakeholders working cooperatively and in partnerships (East African Community Secretariat, 2017, 2018). Similarly, school-child protection agencies’ collaborations have been observed to be a promising educational reform that can enhance the well-being of children (Barnes et al., 2017; Hood, 2019). Child abuse and neglect have been highlighted to be one of the most harmful to children’s growth and development during the initial stages of infancy (Albuquerque et al., 2020; Toth & Manly, 2019). Therefore, collaborations among professionals and agencies have progressively remained a constructive and significant mechanism in promoting child safety and protection services (Cooper et al., 2016; Albuquerque et al., 2020). Similarly, the authors highlight child protection practices as essential for creating safe and nurturing environments in which children can grow, learn, and thrive to their full potential. By implementing effective child protection strategies and interventions, communities can uphold children’s rights and ensure their safety and well-being as a priority (Albuquerque et al., 2020).

According to the results in Table 2, over 75% of the participating schools didn’t have any child protection policies in place, and schools were not collaborating with local leaders to formulate such policies and by-laws. Neither did they work with the parents. Yet there are several cases of child abuse, most especially in the numerous informal settings within the three divisions of Kira Municipality, Bweyogerere and Namugongo Divisions (Tetui et al., 2021). It is the reason that stakeholders need to work in collaboration to come up with child protection policies and bylaws to mitigate the acts of child abuse. This would save children from facing any effects of abuse. The teachers and adults around the child must understand the signs of child abuse. Identifying them by individuals will enable stakeholders to appreciate the availability of the gaps and ensure early interventions are put in place. Besides that, stakeholders must get to know the signs that reflect children who have been abused. Some of these include mysterious changes in conduct/character, such as becoming reserved, hostile, and imprudent.

Some children may be observed to have very few friends, be less connected with siblings/parents and other family members, have untidy appearances, have poor sanitation/dirty clothes, be constantly annoyed, and have unsuitable conversations. Therefore, everyone has to protect children, safeguarding them from danger and promoting their safety and well-being. This would help them flourish, be happy, and reach their full potential. Safety and protection of children right from birth is like protecting the country’s future. It was noted during interviews that most respondents believed that school-local leader collaboration plays a significant role in reinforcing the safety and protection of children right from their homes to school. They observed that apart from parents paying fees, they are very reluctant for the safety and security of their children.

Conclusion

The study concluded that school-child protection agencies’ collaboration enhances child protection practices in schools. Additionally, comprehensive child policies that address the various forms of abuse, neglect, and exploitation need to be developed and implemented. Such policies should be regularly updated and integrated into school operational frameworks.

Establishment of confidential and accessible reporting mechanisms for children, parents, and teachers to report concerns of incidents of abuse. This can include hotlines, suggestion boxes, or designated child protection officers. It is vital to support the implementation of digital literacy and online safety programs to educate teachers, parents, and children so that they can safely use technology, recognize online threats, and protect personal information.

It is significant to provide access to mental professionals, for instance, child psychologists and counsellors, who can be able to offer support to children experiencing trauma or emotional distress. For example, this could include on-site counselling for all stakeholders within the pre-primary schools and external community. Or the creation of partnerships with local mental health organizations. Additionally, it would be imperative to empower teachers with the skill to handle minor issues. This would also include conducting regular safety audits of school facilities to identify and mitigate risks and offering orientation workshops and training for parental and community members on child protection, positive parenting techniques, and recognising signs of abuse. This could empower the extensive community to play an active role in safeguarding children and their families.

Implementing early warning systems to identify and address potential risks to children. This entails closely following up on attendance patterns, behavioural changes among children, and numerous indicators of child abuse, distress, or neglect. Similarly, teachers and other stakeholders must develop strategies to protect vulnerable groups. For instance, children with disabilities, refugees, or those from marginalized communities. This includes tailor-made support programs and ensuring inclusivity in all school activities. We need to include social-emotional learning programs in the learning areas of both teachers and learners so that they can develop emotional intelligence, resilience, and conflict-resolution skills.

Finally, it is important to provide ongoing training for teachers and the entire school staff on child safety and protection issues, including recognition of signs of abuse, appropriate intervention strategies, and legal responsibilities. This will help create a vigilant and informed workforce.

Recommendations

First and foremost, teachers and educators should understand the roles and responsibilities of child protection agencies. They must know who to contact and the appropriate protocols to follow when reporting concerns. Educators should create clear communication strategies with the local child protection agencies and the designated points of contact within the school and the agencies to ensure timely and effective communication. Educators should be able to participate in joint training sessions with child protection agencies to build mutual understanding, trust, and shared language around child protection issues. Similarly, developing a collaborative framework that includes regular meetings, shared goals, and agreed-upon procedures for handling child safety and protection cases is imperative. The framework must be documented and understood by all the various stakeholders involved. Educators should ensure they have comprehensive child protection policies that are well aligned with the ones of the child protection agencies. The policies should be regularly updated and communicated to all stakeholders, including parents, staff, learners, and agencies. The educators should periodically work closely with the child protection agencies to conduct risk assessments within the school. This would help to identify potential risks and develop strategies to mitigate them. It is also essential to create a safe and supportive environment for children and staff, including other stakeholders, to enhance the reporting of concerns. Educators should ensure that there are clear, confidential conduits for reporting and that all reports are treated seriously and acted upon punctually. Educators should ensure that child protection workers jointly develop work plans that promote child safety and protection, train and build educators’ capacity on child protection issues, increase resources and financial support to promote child safety and protection and advocate for laws and policies that promote children’s rights.